Bend, Don’t Break: A Memoir of Endurance, by Frank O’Mara. (The O’Brien Press. April 19, 2024)

Frank O’Mara and I have three things in common: a) we’re both Irish citizens, b) we both competed in track and field in college, and c) we both have Parkinson’s disease.

The commonalities only carry so far, though. Take the issue of Irish citizenship. O’Mara was born and raised in Ireland’s County Limerick; I’m a Midwestern American boy, a product of the “I-states”: Iowa, Indiana, Illinois. He became an Irish citizen at birth, while I claimed Irish citizenship only recently, “through descent.” My maternal grandfather, who emigrated to America in the 1910s, was a Limerick man, like O’Mara, while my maternal grandmother hailed from County Clare, Limerick’s neighbor to the north. The basic difference between us: O’Mara sounds like an Irishman. Me, not so much.

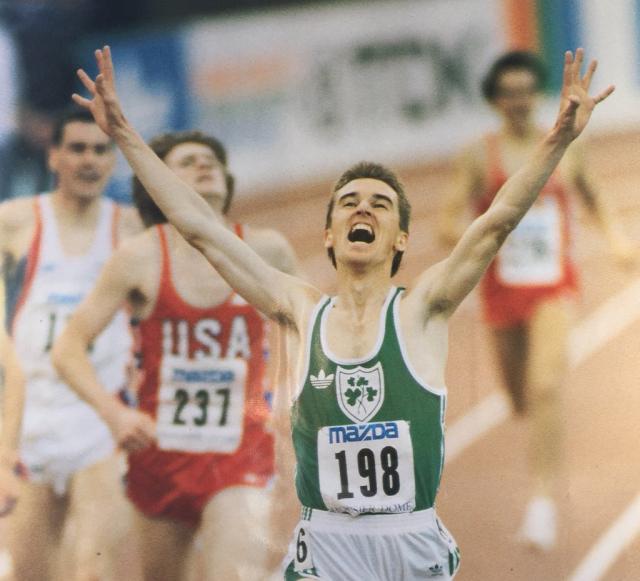

Then there’s the matter of college track (or “athletics” as it’s called in Ireland). O’Mara ran for the University of Arkansas in the 1980s, while I was a shot-putter at Notre Dame several years earlier. He was a key member of a dominant wave of Irish middle-distance runners recruited by American universities in the 1970s, ’80s, and ‘90s (along with Eamonn Coghlan, Sonia O’Sullivan, Marcus O’Sullivan, Ray Flynn, and others). O’Mara went on to win an NCAA title, two World Championship gold medals, and to represent Ireland in three Olympic Games. In 1985, he was part of an all-Irish relay team that broke the world record in the 4 x 1-mile relay – a record that, nearly 40 years later, still stands.

O’Mara, winning the 3000-meter Indoor World Championship gold medal in 1987.

Me? The peak of my collegiate track career was a second-place finish at the Ball State Relays in my sophomore season. (There were no medals; my prize was a too-small tee shirt.) Frustrated by my lack of progress and fed up with spending so much time in dank, windowless weight rooms with sweaty football Goliaths, I retired from shot-putting that spring. But I’ve kept an intense love for all things track and field ever since.

As for Parkinson’s disease (PD) – well, nobody comes out a winner on that one, but of the two of us, I’ve had the easier go by far. I was diagnosed four years ago, at 67, and my difficulties – mainly speech, swallowing, and a clunky gait – are still manageable. I get around without walker, wheelchair, or cane, and I’m fortunate not to have much of a tremor. And since I was an older man when PD came calling, I haven’t missed much that life has to offer. I watched my kids grow into adulthood before I got sick, and I retired from my pediatric career at a time of my own choosing, not prematurely knocked to life’s margins as so many are when PD strikes at an earlier age.

O’Mara’s course, on the other hand, has been nothing short of nightmarish. After being diagnosed with the early-onset variety of PD, his disease progressed rapidly. He soon experienced the worst symptoms that PD can dish out: severe gait disturbances, full-body tremors, excruciating muscle spasms, speech and language difficulties, complications from medications and treatments, and much more. He was sidelined from running, his great passion, and more-or-less forced into retirement from a highly successful career in the wireless communication industry. He writes movingly – and heartbreakingly – of the impact on his close-knit family, of not being able to parent his three sons, Jack, Colin, and Harry, as much, or as long, as he’d have wished. It is O’Mara’s reaction to his plight, though, his refusal to give in to despair – to “break,” as his title suggests – that makes Bend, Don’t Break such a compelling read.

The book opens with a scene familiar to perhaps all of us with PD: the moment when, after months of denial – stubbornly blaming his persistent left leg weakness on a running injury – O’Mara’s unwillingness to accept his diagnosis crumbles when he comes upon his wife, Patty, and an old friend sobbing in their kitchen. “I couldn’t keep reality at bay any longer,” O’Mara writes. “I had early onset Parkinson’s disease at the age of forty-eight.”

O’Mara tells his story in an engaging, non-linear way, weaving the strands of his life – both pre-PD and now with the disease – into a complete picture of the man at all stages of his life. Remarkably, for one who has lost so much to Parkinson’s, O’Mara’s sense of humor seems untouched. He writes with the dry, self-deprecating wit I came to love during my own childhood, spending holidays with my ex-pat Limerick and Clare relatives in Chicago’s vibrant Irish community.

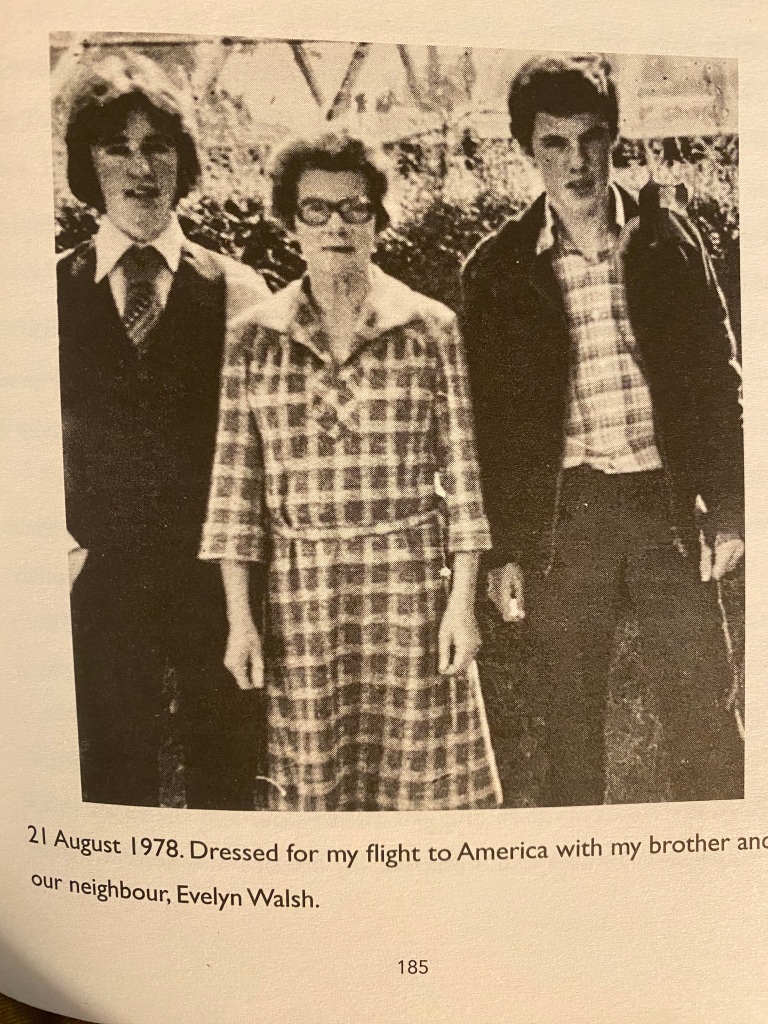

Bend, Don’t Break features a surprising number of funny moments, including one in which O’Mara’s mother buys him a brown, woolen, three-piece suit to wear on the plane for his initial visit to the University of Arkansas, insisting that a nice suit was the key to making a good first impression. Unfortunately, neither young Frank nor his mother understood the oppressiveness of an Arkansas August: “I discovered that brown absorbs heat, and that wool absorbs sweat,” he writes of a layover in Dallas. “Then I encountered the miracle of air conditioning for the first time.” Piece by piece, his suit disappears into his suitcase – replaced by more weather-appropriate attire – until, upon arrival in Little Rock, he sports the under-dressed look of a young man headed for a swimming pool…”[i]f only there was a pool.”

O’Mara (left) and the infamous brown suit, headed for a broiling in Arkansas.

O’Mara’s childhood was marked by two seminal events. The first was his enrollment in an all-boys boarding school – the Dickensian-named St. Munchin’s College1– at age eleven. It was at St. Munchin’s that O’Mara first learned that he was a fast runner. Pressed into service as a speedy “ringer” by a group of older boys hoping to claim possession of a coveted piece of the College’s recreation area for after-dinner games, O’Mara developed the strategies – pacing, sharp elbows, and avoiding “calamity” in the crowded sections of races – that would serve him well in his grownup running career.

The second formative event of O’Mara’s childhood was the sudden death of his father from a heart attack when O’Mara was fifteen. In a poignant section, the author describes his last communication with his hospitalized father – a hand-scrawled letter in which he promised to win the Irish Schools 1,500-meter title the following year. (“Hope you recover,” he signed off, awkwardly, in the way of teenagers everywhere.)

This was a big promise. O’Mara was coming off a string of average-at-best performances (for him) that left him doubting his abilities. But he took his vow to his late father seriously, and through discipline and stepped-up training reached his goal, winning the Irish Schools championship the following year in impressive form, breaking the old record by more than four seconds.

Much of Bend, Don’t Break is devoted to the mature O’Mara’s two main passions: running and the business world. I particularly enjoyed the behind-the-scenes sections on the international track and field circuit of the 1980s and 90s, back when amateurism was still the rule – if only in name – for Olympians. Fans of business success stories will enjoy, too, the high-stakes tale of O’Mara’s tenure as president and CEO of AllTel – the wireless company that once went toe-to-toe with the likes of Verizon and AT&T. This period of O’Mara’s life overlapped with the onset of his PD symptoms, an untimely coincidence that greatly complicated his business dealings.

And then there’s the often-grueling story of the author’s struggles with Parkinson’s, told in straightforward, clear-eyed prose. O’Mara will never be accused of being a Pollyanna; there is neither false optimism nor self-pity in his telling. His description of his disease may be too blunt for someone newly diagnosed, those whose symptoms are still mild and who may well be in the throes of denial. But as someone who only recently passed from denial to acceptance, I find comfort in hearing someone tell his story like it is, particularly someone who has lost so much, but who still sees the value of living his life moment by moment, day by day, and celebrating what small victories PD allows.

It’s typical for a reviewer to gush a bit when he loves a book, to rave about how the author’s story has inspired in him some sort of life-changing epiphany. I can’t say that Bend, Don’t Break has changed the course of my life – I’ve seen what Parkinson’s disease did to my mother and grandfather, and I know that, barring a miracle cure or a timely heart attack, I’m likely headed down that same path.

But I can say that O’Mara, with his love of life, his un-killable sense of humor, his work ethic (he painstakingly typed every word of his manuscript, one keystroke at a time), and his unflinching description of his struggles with Parkinson’s, has inspired me nonetheless. His acceptance of his physical limitations, his determination to challenge those limits, his unembarrassed embrace of his wide circle of family and friends – and his assertion that without that circle he wouldn’t have survived – have made me see my own situation differently.

I’ve always been the physically strong one, the guy who hoisted the heavy stuff, who helped carry others as their bodies failed. It has been very difficult for me to accept the fact that I’m the one needing help now, whether it’s when I stumble, or mumble, or can’t manage those damnably small cuff buttons by myself. I’ve wasted a lot of time deflecting that help, trying to convince everyone – myself, mainly – that I’m just fine, thanks.

Frank O’Mara learned early in the course of his disease to surround himself with the people who loved him and were willing to help. And he took risks, making plans for an uncertain future and carrying through on those plans, even as he dealt with the daunting symptoms of his disease. (I won’t spoil the book’s ending, but it involves a long, arduous trip and remarkable physical challenges.)

Those are the lessons I’ll take from this marvelous book. My wife and I are planning a European vacation for our 40th anniversary next spring, figuring we’ll deal with any changes in my condition between now and then as they arise, and I’m going to start my looong-delayed second book.2 My new mantra: Yes, someday I’ll need a wheelchair, but today is not that day.

And I’ll drop the ‘I’m fine’ act and accept assistance from those around me. Thanks to Frank O’Mara and Bend, Don’t Break, the next time I need help rising from a chair, or un-wedging myself from an overstuffed couch, I’ll gratefully reach out to the hand that’s offered.

_ _ _

Footnote:

- St. Munchin (7th cent A.D.), the patron saint of Limerick, is believed to have been the first Bishop of Limerick, although little trace of him can be found in the historical record. He seems to have been a peculiar choice for a patron saint. According to one source, he is renowned for having cursed the citizens of Limerick for not helping him build his church. (Apparently, they forgave him.)

- My first (and, so far, only) book, Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History, and the Wonder of Childbirth (Ballantine Books) was published in 2009. There’s science, history, memoir, and humor, and more about my family members than you may care to know. Got a lot of great reviews, and there’s a Japanese edition if you’re tired of English. You really should buy a copy!

Mark, Another great and inspiring blog piece. In no small measure do your reflections on Frank mirror the spirit you yourself have shown to the world as you cope with Parkinson’s. I am glad to hear you are more willing to accept the extended hand as I’m sure there are very many glad to extend it to you.

Thanks for sharing. Pauline

LikeLike

Yet another magnificent column. Filled with humor and meaning. So glad to read such well crafted prose from a master.

LikeLike

Thanks, Ritch! This was a fascinating book for me on several levels: Ireland, track, Parkinson’s. awkward adolescence… Glad you liked it!

LikeLike

I just read your blog on BDB and am impressed how well you got my story. You are a fine writer and your commentary read like prose. I loved it. Thanks for noticing and sharing.

Frank O’Mara

LikeLike

Frank – thanks for your reply and for the kind words about my review. I confess I wasn’t so keen on reading BDB at first – I figured it would be too depressing, given that I’m headed down the same path. But my cousin Nancy L***. (Dan L***’s wife) told me a bit about your life and struggles, so I thought I’d give it a try. (Nancy, as you probably know, can be quite persuasive…) I’m glad I did – it’s a great book, from start to finish.

I can relate to the physical effort of writing, too: I wrote a nearly 400-page book, pre-Parkinson’s, with three fingers. (To be clear here, I do actually have ten fingers; I just never took a typing class.) Nearly killed me. I can’t imagine doing that with PD and only one finger. Incredible.

Thanks again. I hope to see more of your writing in the future.

Best,

Mark

LikeLike