“Dr James Parkinson (1755 – 1824)

Born 11 April 1755, James Parkinson is most famous for his essay ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy’ in 1817, which first recognised Parkinson’s as a medical condition.”

– James Parkinson’s biography (in its entirety) on the World Parkinson’s Day website

*****

Parkinson’s Europe established World Parkinson’s Day in 1997 to focus the world’s attention on Parkinson’s disease, the people who live with it, and current research in pursuit of better treatments and, ultimately, a cure.

World Parkinson’s Day is celebrated every year on April 11 – James Parkinson’s birthday – and honors the man who put my current diagnosis on the medical map. But to remember Parkinson solely for his eponymous disease (and with a single-sentence biography) would be to shortchange both him and us. He was an immensely talented man, one who exerted considerable influence on late-18th and early-19th century British science, politics, and society. With this post, the second of I’m-not-sure-how-many, I continue the story of James Parkinson.

*****

If, shortly before his death in 1824, you had asked James Parkinson to guess which of his life’s many accomplishments would still be celebrated nearly 200 years into the future, he likely would have chosen his research on fossils (of which he was considered a world expert) and geology. In honor of his contributions to the field, Parkinson had a number of fossilized creatures named for him, including the doubly-named ammonite, Parkinsonia parkinsoni. He is rightfully considered one of the founders of scientific paleontology.

Or, he might have picked one of his many medical successes: pioneering work on cardiac resuscitation (he was the first physician to be credited with “bringing back to life someone considered dead”), lightning-strike injuries, hernias*, appendicitis, gout, and a number of infectious diseases, including rabies and typhus.

He might also have chosen his advocacy on behalf of the mentally ill, particularly his reforms of Britain’s “mad-houses,” or his efforts to alleviate some of the era’s many other social ills: child abuse, child labor, and abysmal medical care for the poor.

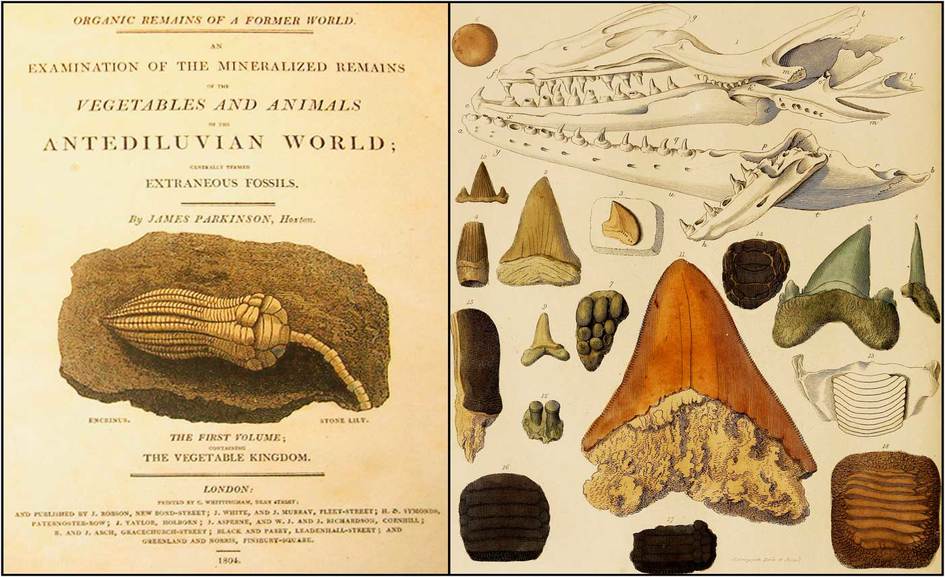

A best-selling author in Britain and the United States, Parkinson might assume that you’re referring to one of his many books – say, his popular volumes on parenting, medical advice, and other health-related topics; The Chemical Pocket-Book (a chemistry textbook); or his magnum opus, Organic Remains of a Former World – a richly illustrated, three-volume treatise on the identification and interpretation of fossils. Organic Remains drove much of early-19th-century Britain’s “fossil-mania” and inspired the poets Alfred Lord Tennyson, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron.**

“Organic Remains of a Former World” (1804)

Finally, he might have chosen his political activism as the thing people would still be talking about in 2023. A champion of the common man and supporter of the French Revolution, Parkinson was called to testify by British authorities in 1795 in an alleged plot to assassinate the King and was nearly charged with treason himself. Appearing before a suspicious Privy Council – a tribunal that included, among others, the prime minister and attorney general of Great Britain – Parkinson talked his way out of trouble, narrowly escaping a long sentence in one of London’s dismal prisons, deportation to Australia, or even execution.*** His skill and courage in out-debating the Council members, as recorded in the Council transcripts, is remarkable.

Imagine his surprise, then, when you tell him that no, it’s none of those things…the accomplishment for which you’ll be best remembered centuries from now is (drumroll…) Parkinson’s disease! An awkward moment passes. You’d have to excuse his look of bafflement, as he wouldn’t have any idea what you’re talking about. Because, you see, Parkinson’s wasn’t “Parkinson’s” to Parkinson; “his” disease wouldn’t be named for him until a half-century after his death.

The pamphlet he wrote about the disease, titled “An Essay on The Shaking Palsy“, was published in 1817, a few years before he died. It was based on Parkinson’s insightful observations of just six individuals, including three he only saw from time to time, walking through the market near his home. While other physicians had described individual signs and symptoms of the malady – tremors, stooped posture, slowness in moving, and such – Parkinson was the first to recognize that these were all part of a single, slowly progressive neurologic disease. After publishing “An Essay on The Shaking Palsy,” Parkinson tended to downplay his key role in its discovery – to his mind, he hadn’t discovered the cause or a cure, so what was there to crow about?****

Parkinson could be forgiven for not guessing the reason we still celebrate his birthday today. Compared to discovering traces of vanished worlds, writing best sellers, improving medical care for ordinary people, or verbally jousting with a prime minister intent on chopping him into pieces, “The Shaking Palsy” was more footnote than main event. At least that’s how Parkinson might have seen it; to me, the man and his many contributions to humanity are a source of wonder.

So, Happy World Parkinson’s Day! Please give a thought to James Parkinson and his remarkable career on April 11 – his 268th birthday. Then visit the Parkinson’s Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the American Parkinson’s Disease Association, the Davis Phinney Foundation, the Parkinson’s Association of Northern California (PANC), or the websites of one of the many other PD advocacy groups to learn how you can help in the fight against Parkinson’s disease!

(Next up in the “History of James Parkinson” series: If we’re going to take the full measure of James Parkinson’s magnificent career, we’ll need to start from the beginning. And that beginning begins in Parkinson’s lifelong hometown of Hoxton, a small village located a mile north of Bishopsgate, one of the medieval entry-points into the city of London…)

_____

*Parkinson’s hernia truss design (1802) is the template for today’s trusses, with only a few modifications.

**Shelley collected Parkinson’s writings; Byron’s poem Don Juan makes reference to Organic Remains; and in the poem, In Memoriam, Tennyson gazes at fossils encased in the walls of a stone quarry and muses: “From scarped cliff and quarried stone/ She cries ‘A thousand types are gone:/ I care for nothing, all shall go… (Kind of bleak, that.)

***The punishment for treason was grisly: the condemned was “hanged, drawn, and quartered,” a brutal form of execution in which the victim was hanged from a gallows, then disemboweled while still alive (drawn), and finally beheaded and dismembered (quartered). (Way bleaker than Tennyson…)

****He’d also be shocked, no doubt, to learn that a cure for Parkinson’s disease still eludes modern science.

What an amazing contributor to humanity. I really enjoyed reading about his life and look forward to the next installment.

LikeLike

Thanks, Maxine!

LikeLike