Introduction: Why don’t they name diseases after people anymore?

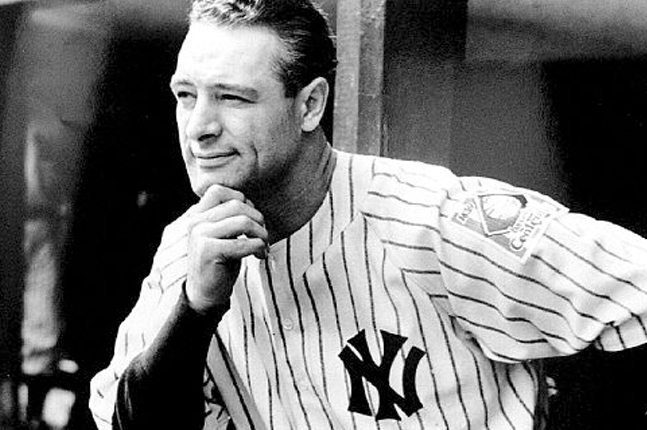

My aunt died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease (better known today as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—ALS) in the 1980s. A cruel disorder that progressively weakens the muscles of its victims until they can no longer move or breathe, her death was a grim, protracted, miserable ordeal, much like Gehrig’s a half century earlier. Gehrig, a New York Yankee legend and one of the greatest baseball players ever, was just 37 years old when he died in 1941.

If you’ve never heard of Lou Gehrig, or only have a vague idea of who he was, you’ve hit on one of the reasons that diseases are rarely named for individuals anymore. People – even once-world-famous ones like Gehrig – eventually fade from public memory. Gehrig went from being the New York Yankees’ “Iron Horse” in his prime, to the face of a pitiless disease for a generation or two, to something of an afterthought today. *

Lou Gehrig (1903-1941): An American icon

There are other reasons for shying away from naming diseases for people, including the fact that the person credited with discovering the disease often didn’t actually do so, or at least, not by themselves. Medical archives are filled with the unrecognized contributions of junior researchers—often women—and scientists of color. White male scientists, particularly those in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, had no qualms about hogging all the credit for themselves. **

Then there’s the issue of the namesake’s behavior, particularly when that behavior involves war crimes. Take the case of Hans Reiter, a German physician who first described what came to be known as Reiter’s syndrome: a triad of arthritis, urethritis (a painful inflammation of the urethra), and uveitis (a painful inflammation of the eye). Reiter’s syndrome was the term I memorized in medical school in the 1970s; I never gave a second thought to who Reiter was, or what he did with the rest of his life.

But Hans Reiter had a very dark side: a fanatical Nazi, he was the physician in charge of “quality control” at the Buchenwald concentration camp during World War II. There, he directed hideous research on prisoners, many of whom died. (His experiments with a failed typhus vaccine alone killed more than 200.)

Hans Reiter (1881-1969) – A really bad man

As if murdering innocent people weren’t enough, it also turned out that Reiter wasn’t even the first individual to describe “Reiter’s” syndrome – he was about 200 years late on that one – and that he was way off base as to the cause (he blamed a syphilis-like bacteria). Although it took several decades, the medical community ultimately booted Reiter and renamed his syndrome reactive arthritis. ***

So, why has James Parkinson been spared the bum’s rush? Why does he still own his eponymous disease, while bad actors like Reiter (and some good ones, too) have been consigned to history’s dustbin? As we’ll see in upcoming posts in the “History” series, Parkinson’s longevity is due to a combination of modesty, timing, and a fascinating, incredibly productive life.

_____

* In fairness, ALS was already ALS long before Lou Gehrig. (It was named in 1874 by the French physician Jean-Martin Charcot; coincidentally, Charcot also popularized the term, “Parkinson’s disease.”). The huge public outpouring of grief following Gehrig’s death led to the Lou Gehrig’s Disease/ALS connection—a link that no doubt gave a boost to ALS fundraising efforts.

** One example: Alice Ball (1892-1916), a Black researcher at the University of Hawaii, developed the first effective treatment for leprosy. When she died at age 24, possibly due to a lab accident involving chlorine gas, a white male colleague claimed the discovery for himself. It took the University of Hawaii nearly 90 years to formally recognize her work.

***Reiter spent a shockingly brief time in prison for his deeds, gaining early release possibly in exchange for helping the Allies with their biological warfare programs. (Yikes!)

I never thought I would be interested in learning about the namesake of a disease let alone Parkinson’s Disease. So now you have piqued my curiosity, Mark. I am actually looking forward to part 2.

LikeLike

Stay tuned!

LikeLike