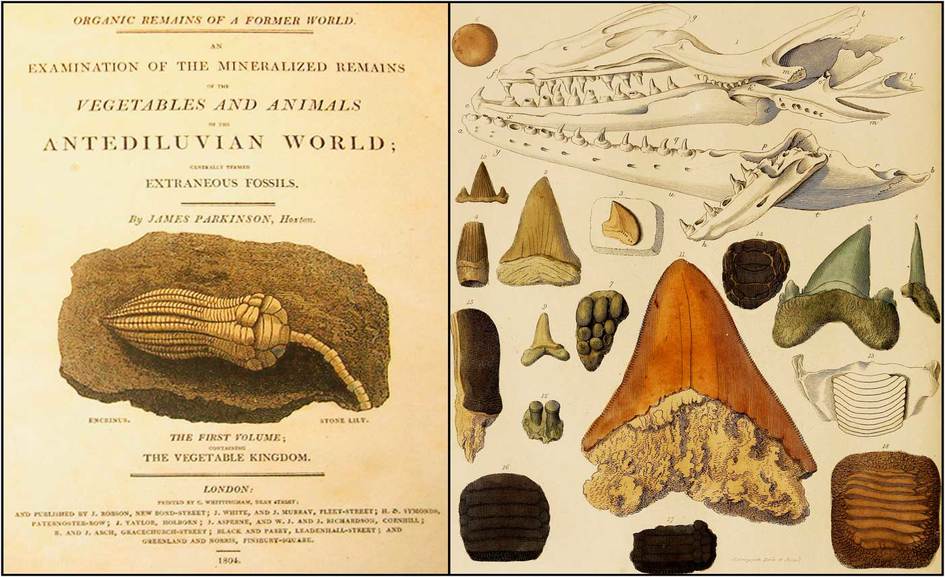

In an earlier post I wrote about James Parkinson, the British physician who, in 1817, described what would later be called Parkinson’s disease. He had a multi-faceted, truly remarkable life – sort of a British Benjamin Franklin. Parkinson was, in addition to being a renowned physician, a political radical, a best-selling author, an inventor, a crusader for the mentally ill and against child labor, and one of the world’s foremost experts on geology, paleontology, cardiac resuscitation, rabies, and lightning strike injuries.

Given all that, you’d figure it would be easy to discover what the man looked like. After all, museums, palaces, and private mansions throughout Great Britain are festooned with 18th and 19th century oil portraits of virtually every British man (and some women) of means. Yet, inexplicably, no portrait of Parkinson survives.

Fame certainly wasn’t a prerequisite for portrait-sitting in those days. This fact is brought home poignantly by the abundance of paintings of now-unknown subjects – people who, during their lives somehow merited a grand portrait but then were forgotten, quickly or otherwise. Take the case of “An Unknown Man” by the obscure British portraitist Tilly Kittle (1735-1786).1

“An Unknown Man.” (Artist: Tilly Kittle. Date: unknown.)

In Kittle’s rendering, Unknown Man is a plump, baby-faced, apparently wealthy young fellow, surrounded by props – the books, the Roman column, the quill poised in the the inkwell – that would imply a man of some learning and power. His delicate hands, though, hint at a life of epicurean leisure, likely lived at the expense of servants and peasants. His prominently (proudly?) displayed belly, which threatens to overpower the buttons of his waistcoat, suggests nothing so much as a man about to give birth to twins. Taking a wild stab, I would guess that the young Mr. Man inherited his riches.2

For decades everyone “knew” what James Parkinson looked like – or at least they thought they did. They assumed he was the square-headed, bushy-faced man in the accompanying photograph:

Dr. Parkinson, I presume…

In truth, while he was a James Parkinson, he was not the James Parkinson. The James Parkinson in the photo was, in fact, an Irishman who sailed to Australia during the 1850s gold rush and wound up a Tasmanian lighthouse keeper. He was born eight years after “our” James Parkinson’s death. The tipoff? The first photograph of a human face was taken in 1839, more than a decade after Dr. Parkinson’s death.

This lack of a portrait seemed unjust to me, given the greatness of the man. So, this being the 21st century and all, I decided to put technology on the case – specifically the much loved and loathed new versions of artificial intelligence. I gave DALL-E, the artsy part of openAI’s suite of A.I. programs, its marching orders: “Paint an oil portrait of Dr. James Parkinson, British, in the 18th century style of Tilly Kittle.”

And here’s what I got…

James Parkinson. (“Artist”: A.I. DALL-E, 2023)

Hmm. Looks suspiciously like a slimmed down, age-progressed version of “An Unknown Man,” right down to the left-eyed, thousand-yard stare3 and the proto-1960s flip hairstyle. I thought A.I. would be a bit subtler in its plagiarizing.

I’m not sure if Tilly Kittle would feel flattered or litigious. No doubt some future A.I. iteration will answer that question for him…

_____

1 Tilly Kittle was a British portrait painter who, after middling success in his early career in England, struck out for India, where he grew rich painting “nabobs and princes,” according to his bio in The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. He returned to London after a decade, where he soon acquired a wife, a mountain of debt, and few clients. After fleeing to Ireland to escape his creditors, he decided to try his luck in India again, but this time died en route, somewhere in present-day Iraq. According to the Oxford Dictionary entry, Kittle is best remembered for ranking “fairly high among the lesser portraitists of his time.” Ouch!

2 Kittle may have been a more perceptive capturer of his subjects’ inner selves than he’s been given credit for. Try this experiment: click on the larger copy of “An Unknown Man” here, cover one side of his face and then the other. You’ll see the right side shows an affable-if-entitled trust fund baby; the left side, meanwhile, reveals the thousand-yard stare of a fellow who just learned, say, that he’s about to give birth to twins.

3 Try the left-right face experiment described in footnote #2 on the A.I. portrait – same result!