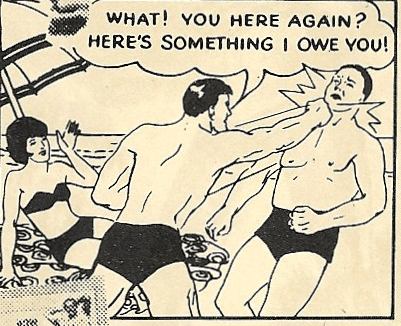

There’s a young man who’s been working out at my health club for a few months now. When I first saw him he was sapling-skinny, with scarecrow hair, owlish eyes, and black, square-ish, never-in-style eyeglass frames. I had sympathy for him—I took care of a lot of teen boys wrestling with body image issues in my pediatric career. Dressed in baggy sweats, he could have been the inspiration for one of those 1950s Charles Atlas bodybuilding ads—the 97-pound weakling who gets sand kicked in his face by the muscle-bound beach bully (1):

And sure enough, just like Atlas’s scrawny “Mac”, the young man at the health club soon transformed his body. His determination was a thing to behold, as he followed an exhausting routine of curls, bench presses, squats, pull-downs, and more, adding a bit of weight to the bars each week. His broomstick arms sprouted biceps that steadily grew; pleased with his own progress, the young man took to striking furtive poses in the mirror that covers the back wall of the weight room.

He’s now well on his way to becoming a true Charles Atlas “new man.” Where he once crept into the weight room, he now strides in with confidence. His t-shirt has gotten tighter in the chest and biceps. He’s weed-whacked his hair into a fashionable ‘do’. He’s even got new, au courant glasses. Woe betide the bully who inspired this transformation—he’s in for a good girlfriend (or boyfriend)-witnessed chin-bopping sometime soon:

A righteous ‘bop’…

I’ve had to fight the urge to share my Parkinsonian learning with the young man. I’d like to tell him that all that iron he’s been pumping has made his brain stronger, too. Why, he’s got a zillion new neural connections all over his noggin – in the basal ganglia, the zona pellucida, the locus ceruleus, you name it! But he’s a twenty-something guy; who cares how good your brain looks at that age? I figure he’d just take me for a crazy old man. Which, I am.

+++

Here’s an old adage that I just made up: What’s good for the body is good for the brain. It’s true, if maybe not too catchy. When it comes to Parkinson’s, vigorous exercise of any kind, whether running, swimming, brisk walking, cycling, boxing, dancing, strength training à la Charles Atlas—basically, any form of exercise that gets your heart pumping—actually stimulates the growth of new neurons (brain cells) and strengthens connections between neurons in many parts of the brain. This makes for speedier and more efficient communication between areas of the brain, something of great importance to those of us with Parkinson’s.

But, really, there’s no anti-Parkinson’s magic going on here. Moving your body is good for all brains, not just the PD kind. The mechanisms behind the benefit are the same for the afflicted and the un-afflicted alike. It’s just that those of us with PD are starting in a neurological hole—we’ve been losing dopamine-secreting neurons for years, maybe even decades, before we’re diagnosed. Exercise can help you dig your way out a bit, or at least slow down the rate of decline.

How does exercise work its magic on the brain?

I learned back in high school biology that the adult brain was more or less a done deal, a mysterious, gelatinous blob that bossed around the body via an old-school scheme of stimulus and response. You were born with a finite number of neurons in your brain; our teacher told us, and once they’re gone, poof, they’re gone for good. I remember even then thinking that didn’t seem quite right—if head injuries or strokes destroyed brain tissue for good, I wondered, how did some people learn to walk or talk again afterwards?

When I reached medical school, I learned that, rather than a rigid, finished product, the brain was in fact plastic. (No, not in the single-use-shopping-bag sense; neuroplasticity is defined as the ability of the nervous system to reorganize itself, to change its structure, functions, or connections after injury or in response to external stimuli.) The brain has a remarkable—but not unlimited—capacity to heal itself.

The principle of neuroplasticity is critical to brain health in the neurotypical (aka, “normal”) individual and even more so in people afflicted with Parkinson’s disease. There’s currently no cure for PD—no way to undo the damage that’s been done by whatever the heck is causing the disease—and available medications provide only symptomatic relief. Exercise, though, can actually slow PD’s inexorable march. That’s why every newly diagnosed PD patient hears a nearly constant mantra from neurologists, therapists, and everyone else in PD world: You gotta get moving, bud! Movement is medicine!

And they mean “get moving” quite literally, because body movement sends a signal to both the neurotypical and PD-afflicted brain to crank out increased amounts of a molecule known as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF in turn stimulates the growth of neurons in areas of the brain that are active. It’s nature’s way of building up the neuronal pathways that a healthy body uses most, while not wasting energy on those that are neglected.

Of particular importance for people with PD, movement-stimulated BDNF production promotes the growth of neurons that manufacture dopamine, the neurotransmitter that controls and fine-tunes muscle activity and coordination. (Low levels of dopamine are responsible for the tremors, slowness, and rigidity characteristic of PD.) A virtuous cycle is thus created: body movement increases BDNF and dopamine production—especially in areas of the brain that control movement and balance—which in turn make it easier for you to move, which then stimulates the brain to produce more BDNF and dopamine…and so on. It’s a variation on the old saying, “use it or lose it”: Use it (move your body!) and grow it (dopamine production).

What type of movement or exercise is best?

Good question! But this post has gotten pretty long, so how about I answer that one in my next post?

Stay tuned!

—–

Footnote:

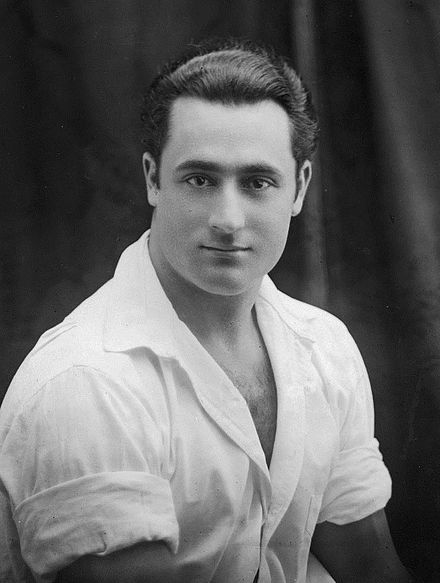

1) Charles Atlas (1892-1972) was born Angelo Siciliano in Calabria, Italy. He emigrated to New York, in 1904, where as a teenager he became fascinated with the bodybuilders and strongmen at a Coney Island circus.

Atlas (he legally changed his name in 1922 after being told he resembled the statue of Atlas atop a Manhattan hotel), a late bloomer, described himself as the original “97-pound weakling” who got himself doubly humiliated one day when a muscle-bound guy kicked sand in his face at the beach as his girlfriend looked on and ridiculed him. Vowing revenge, Atlas whipped himself into muscle-man shape, a transformation that earned him a) the aforementioned revenge, in the form of a beach-bully beat-down; b) a job as a bodybuilder on Coney Island, c) a string of titles, including “America’s Most Handsome Man” and “America’s Most Perfectly Formed Man” and d) a lucrative side gig as a sculpture model. (Among many other artistic commissions, he posed for the statue of Alexander Hamilton that still stands outside the U.S. Treasury building in Washington, D.C.)

Charles Atlas is probably best remembered today for the wildly popular, full-page comic book advertisements for his eponymous body-building course. The story line in the ads hardly changed over the decades: a scrawny, dweeby-looking young man (typically named “Mac,” “Joe”, or “Jack”), dressed in ill-fitting, high-waisted swim trunks, sits with his shapely girlfriend on a beach towel, when, seemingly out of nowhere, a macho bully insults him (“Hey skinny! Yer ribs are showing!”), slaps him, and then kicks sand in his face, while Joe’s girlfriend snickers and further deflates his ego (“Oh, don’t let it bother you, little boy!”). Joe stomps angrily home, kicks a chair, vows revenge, then sends in a coupon for a free Charles Atlas booklet, and –lo!–two panels later he’s back on the beach with muscles popping out all over the place, bopping the bully in the jaw to the lusty approval of his fickle girlfriend (“Oh, Joe!” she coos as the bully skulks away. “You are a real he-man after all!”)

But a moral conundrum is left hanging in the air: Did Charles Atlas really make Joe a better man, or did he just create a new bully?