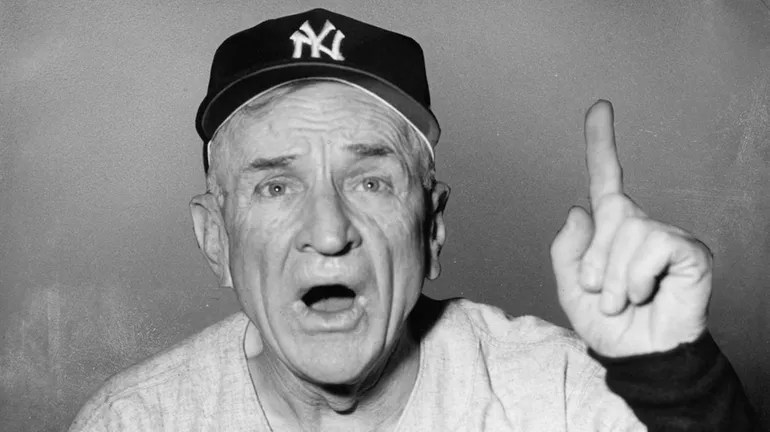

“I’ll never make the mistake of turning seventy again.”

Casey Stengel (1890-1975), blaming his 1960 firing as New York Yankees manager on a “youth movement.”

It’s Monday. I’m back at my favorite coffee spot on Hayes Street, a couple of blocks down from the San Francisco Opera House and the SF Ballet School, waiting for Elisabeth to finish her afternoon dance class. As usual, I’m surrounded by young people – I’m easily the oldest customer here by 20 years or so. Today I’m in observation mode, watching how techie-youth move, taking inventory of any apparent aches and pains they may exhibit. After an hour, a conclusion: they don’t seem to have any, as far as my trained-but-retired doctor’s eye can tell.

Oh, to be young again! I watch them jump up from their chairs to order food, or grab drinks, or to greet one another at the door with hugs and air smooches. They seem improbably flexible, impossibly fluid in movement – the exact opposite of a “movement disorder.” This is especially remarkable, since they likely spend the bulk of their days slumped in front of one screen or another. But they’re still a good decade or so from that catching up to them. For now, life is all loose and boing-y and physically fabulous.

Now, imagine for a moment that the coffee shop demographic suddenly flips, and the tables are filled with people my age—boomers all, in their mid-60s to mid-70s. There’s a different vibe. The noise level has dropped considerably. People don’t jump up for their food; they call for waiters. And one topic of conversation is heard at every table: health, or the lack of it. From the life-threatening (cancer, heart disease, hypertension), to the life-altering (diabetes, cataracts, bad knees and hips), to the nuisance level (aches and pains, “senior moments,” flatulence), who’s-got-what and how-do-you-treat-that discussions dominate.

Me, I’ve got all the basic aches and pains that come with having arrived on the planet at the dawn of the (first) Eisenhower Administration. My neck twangs as I type this, my knees are a bit sore from my Ballet for People with Parkinson’s class, and my shoulder aches for reasons I can’t recall. (Old football injury, ca. 1970?) My balance is a bit dicey, too. I tend to blame a lot of my physical woes on Parkinson’s, but I wonder: how much of this do I owe simply to being seventy years old? In other words, if I could subtract Parkinson’s from my personal health equation, how much different would I feel today?

Here’s the problem: a lot of otherwise neurologically normal-for-age older adults show mild Parkinsonian signs and symptoms. Many elders are stiff of trunk or limb, move at a turtle-like pace, or have problems with gait and balance. But by definition, the sum total of their signs and symptoms falls short of the accepted criteria for making the diagnosis of PD.

I recently started having episodes of vertigo—abrupt, severe (and mercifully brief) bouts of the “whirlies,” in which the room spins and I have to grab hold of whatever is nearby to keep from falling. These bouts are more or less predictable. When my whirlies hit, it’s always positional: I’m either leaning down to pick something up from the floor or rolling over onto my side in bed. I’ve found that I can get it to stop quickly by changing position.

My first instinct was to blame the vertigo on PD, since the two often come together. But then, in reading and discussing my symptoms with my neurologist and physical therapist, it became clear that I was suffering from Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, an age-related condition that involves the balance centers in the inner ear. It’s a pain, but it’s not related to PD.

But it really doesn’t matter what’s causing my vertigo. A hard floor is a hard floor, no matter what got you there. That’s why the advice you’ll get from movement disorder professionals about preventing falls at home is pretty much the same as you’d get from anyone who works with the elderly. The same goes for any number of symptoms – constipation, to name a common one – that overlap both PD and just getting older. The treatments are very similar, PD or no.

The good news? My vertigo didn’t signal a new milestone in my PD progression. The bad news? I’ve got BPPV. The sorta-good news? At least BPPV is something new to wow my boomer coffee shop friends with… if I can get a word in edgewise while they’re busy bemoaning their prostates, that is.