My mother, Peg Sloan, died in 2017 of Parkinson’s-related aspiration pneumonia. She inhaled some thick pudding, one of the last foods she was allowed to eat as her swallowing grew dangerously uncoordinated, and that set the end in motion. She had been hospitalized with pneumonia several times; this time was the worst, and Mom had decided beforehand to refuse extraordinary measures to keep her alive.

Long before Parkinson’s closed in on her life, Mom had been a writer and editor. She spent her entire professional career at the Kankakee Daily Journal, a small-to-medium-sized newspaper in a small-to-medium-sized town in east-central Illinois.

Starting as an op-ed contributor, she was soon named editor of “Accent,” a lifestyle-themed section of the paper that had long been heavy on the doings of Kankakee’s elite: weddings, engagements, costumed soirees, and the like. Mom dragged Accent out of its rich-folk doldrums and pushed it into the present. By the mid-1980s, just a few years after she took over the editorial reins, Accent had twice been honored by United Press International, including an award for its follow-up investigation of a secretive religious cult near Kankakee that had vanished five years previously, taking the children of several local residents with them.

Mom also wrote a popular weekly “personals” column. Her first published essay was on the trials and tribulations of being a redhead.*1 By her retirement she had written more than 700 columns on a wide variety of subjects, including her Irish heritage, her travels, the sometimes-humbling experiences of a big-city girl who married into a farm family, and—her go-to topic—the ups and downs of raising six kids. My mother’s warm, accessible, often funny writing style won her a devoted readership, syndication in a smattering of small Midwestern papers, and a number of awards. Mom was honored for her columns by the Illinois chapters of the Associated Press and United Press International, and the National Federation of Press Women.

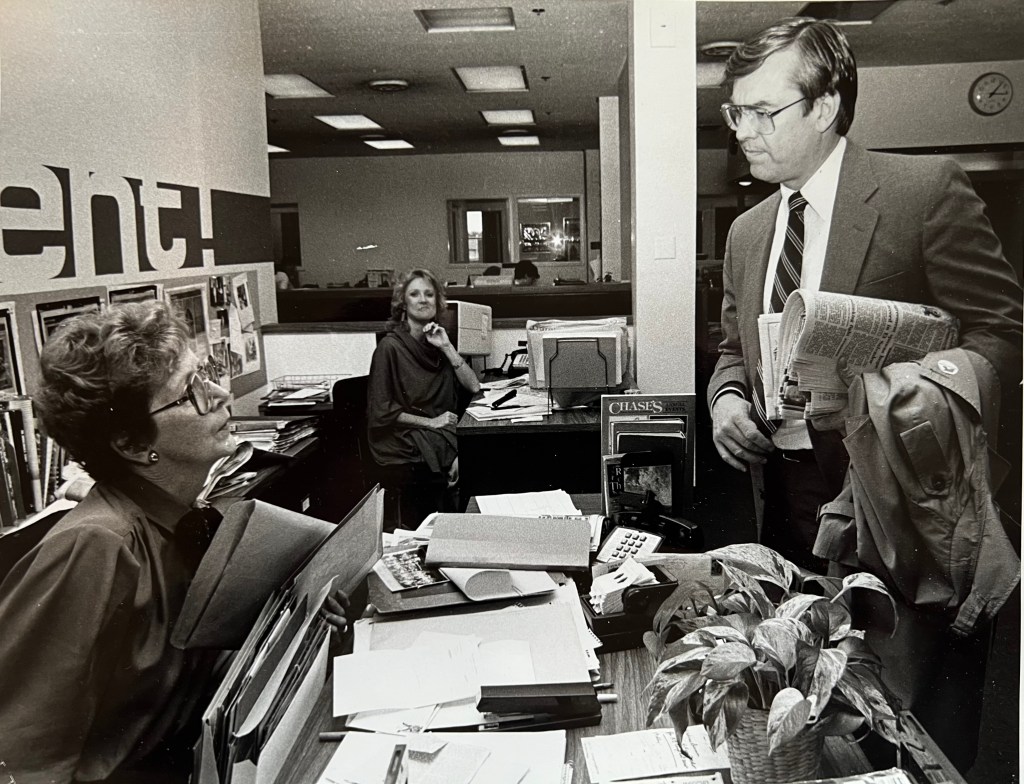

Peg Sloan (left) meets with CBS newsman Bill Kurtis during the investigation of a religious cult near Kankakee, late 1970s. (And yes, that’s the same Bill Kurtis who’s now the announcer, judge, and scorekeeper on the popular NPR program, Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!)

The most remarkable thing about Mom’s journalism career is that it didn’t start until she was in her fifties. Before ever setting foot in the Daily Journal offices, Mom raised the six of us. And when I say that she raised us, she did just that. For nearly thirty years Mom was up to her elbows in mid-century mothering: diapering, cooking, sewing, first aid, PTA meetings, birthday parties, church socials, football Fridays, and laundry, laundry, laundry. Not until the last of us was grown and out of the house (or nearly so – my youngest brother, Chris, abruptly became a “latchkey kid” when Mom joined the Daily Journal a few months before his high school graduation) did she pursue her long-deferred dream.

She told me years later that she had always wanted to be a writer, that if she’d been born a generation later she would have been a journalist right out of school. Mom kept that desire hidden from her kids for decades, but from time to time it slipped out.

I must have been about ten years old when I came across Mom sitting on a stool in the laundry area of our basement, barricaded behind baskets of dirty and/or wet clothes, scribbling with a pencil in a small, spiral-bound notebook.

This was truly strange behavior. One thing to know about my mother: she absolutely abhorred heat and humidity, so for her to spend even one extra mid-July minute in our often-hellish southern Indiana climate—in our stuffy basement with the washer and dryer running, no less—meant that whatever she was working on must have been important. *2

She didn’t notice me at first. I watched sweat run down her cheeks and drip off the tip of her nose. Her soaked blouse clung to her shoulders. I knew adults had heart attacks sometimes—was that what this was? She paused and stared into space for a moment, immobile, then quickly erased a line and started scribbling again. I watched her a minute or so, until I couldn’t contain my concern.

“Mom?” I shouted, loud enough to be heard over the clanking Maytags. “Are you okay?” I touched her arm. “Maybe you should go upstairs and sit by the air conditioner?” *3

Startled by my sudden appearance, she slapped her notebook shut, slipped it into a shoebox with several others, and grabbed a towel to wipe the perspiration from her face. “Yes, let’s get upstairs,” she said with a wan smile. “I’m boiling.”

Later, camped out with a glass of ice water by the air conditioner in her bedroom (I inherited my mother’s hatred of Evansville’s wilting summertime swamp-heat), Mom slipped some rubber bands around her shoebox full of notebooks and slid it high up on closet shelf. My eyes followed the box; she could see I was curious about it.

“I was just writing a grocery list,” she said.

The notebook had been filled with writing. “That’s a lot of groceries,” I said.

“Well,” she said, smiling, “you kids eat a lot of food.” She took my glass to the kitchen to refill it, and that was that.

Mom retired from the Journal in the mid-1990s. When I asked her why she was giving up her column, she shrugged and said, “I guess I’ve said all that I have to say.” Looking back, this was about the same time that her Parkinson’s symptoms first emerged, although she wouldn’t be diagnosed for several more years. I’d noticed that her hands now shook, especially when trying to hold a cup of her beloved coffee. Her once-gorgeous handwriting had shrunk to the point of near-illegibility. Her gait had slowed, and she stooped a bit when she walked. Mom was an elegant, proud woman – I can’t help but think that she could feel her talents slipping away, and wanted to retire while she was still at the top of her game. She wouldn’t have wanted anyone’s pity.

_____

When I arrived at the hospital on the day before Mom died, she was barely conscious, but she was comfortable, thanks to the efforts of the hospice staff. When she saw me she raised her hand, smiled weakly, and said, “Oh, you came!”

I stayed by her bedside that night, as part of a round-the-clock vigil shared with my sibs. Mom was breathing softly, eyes closed, no longer interacting with the world. But I thought she might still hear me, so I read her favorite columns to her, one after the other: the stories of her adored Irish father, the affection that slowly grew between Mom and her no-nonsense farmer mother-in-law, her childhood in a multi-cultural, pre-air-conditioning Chicago neighborhood, her kids—us. She didn’t respond, but she didn’t struggle, either.

The next afternoon, with Dad and her children at her side—just two months shy of their 70th wedding anniversary—Mom quietly stopped breathing. It was Valentine’s Day, my parents’ favorite personal holiday.

_____

*1 – The cons of being a redhead, per Mom: ghostly pale skin, freckles, raging sunburns. Pros: Um, not so many, apparently…

*2 – One Evansville summertime climate example will suffice: There was a section of the Yellow Pages devoted entirely to companies that would come and remove the melted road tar your kids tracked onto your wall-to-wall carpet with their shoes. Road tar in Evansville was sort of like mud in cooler climes, I imagine, but a lot harder to get out.

*3 – We had one window air conditioner for the whole house, in my parent’s bedroom: a boxy Whirlpool colossus that was about as loud as the washer and dryer combined. If you kept the bedroom doors closed all day with the Whirlpool blasting away, the room was tolerably comfortable for sleeping at night. I would often find Mom in her bedroom on summer afternoons, hugging the Whirlpool like a long-lost friend, her red hair blowing in the breeze. The rest of us slept in a converted attic bedroom, which was just as hot as that sounds. (Dad did install a window air conditioner in the attic eventually, but it’s cool-air zone was even smaller than the one downstairs…)